The two principal owners of LaSalle Street Station.

In 1851 the

Chicago and Rock Island Railroad incorporated and began construction of a line between

Chicago and Joliet, which was completed in 1852. That same year the Northern Indiana and

Chicago Railroad reached Chicago, the first Eastern railroad to reach the city.

This 1862 map shows the first station.

The first LaSalle

Street station was constructed at the foot of Van Buren Street at LaSalle

Street and opened on May 22, 1852 coinciding with the completion of the Northern

Indiana and Chicago. The Rock Island began using the station soon after on

October 1, 1852. The NI&C would later become the Lake Shore and Michigan

Southern Railway (LS&MS), a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad,

and the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad (CRI&P). Both companies

shared a right-of-way to the terminal north of their intersection at Junction

Grove, later known as Englewood. There appears to

be no illustrations or photographs of the first station, although it does

appear on early maps. It was probably a

humble structure made of wood, similar to other early railroad stations in the

city’s central business district. With

the rapid growth of passenger traffic a larger station was called for, and

construction of the new building began on April 16th of 1866.

Architect Boyington and his masterwork.

Completed in

November of 1866, it was designed by architect W.W. Boyington. Boyington is

best known as the architect of the iconic Chicago Water Tower. Designed in the

“Franco-Italian” style, the station building measured 542 feet by 160

feet. The balloon type train shed roof

spanned five tracks, three tracks for departing trains and two for trains

arriving. The Howe Truss roof stood 60 feet above the platforms and was covered

with slate. The west side of the building contained a number of rooms for the

accommodations of travelers waiting for the departure of trains. These rooms

connected with the platform within the depot, and fronted on Sherman and

Griswold streets. Each railroad using the depot had baggage rooms, oil and lamp

rooms, conductors’ room, and large waiting “apartments” for ladies and

gentlemen. There were rooms for second class passengers and immigrants, as well

as a restaurant and ladies dining room. The

Van Buren Street facade featured a frescoed entrance hall. On the east side of

this hall were the offices of the Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana

Railroad Company. On the west side of the hall were the offices of the Chicago,

Rock Island and Pacific Railroad.

The fire ravaged remnants of the station.

The Great Chicago

Fire of October 1871 destroyed the station, which was rebuilt and expanded with

additional stories shortly afterwards. From its completion in 1882, the New

York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad (Nickel Plate Road) ran over the Lake

Shore and Michigan Southern Railway from a junction at Grand Crossing

neighborhood north to downtown Chicago, where it had its own terminal south of

LaSalle Street Station at 12th Street. The LS&MS quickly gained

control of the Nickel Plate, and later allowed it into its LaSalle Street

Station as a tenant. The station was also served by a direct link to the

elevated rapid transit system.

The rebuilt and expanded station.

The direct connection with the elevated train was a major advertising point.

On December 20th

1901 the trains using the station were shifted over to Grand Central Station

and the post-fire station was demolished to make way for a new station designed

by the architectural firm of Frost and Granger. The initial plans called for an

8-story steel-framed office building with a station on the first three levels.

By the time construction started an additional 4 stories were added. The construction of the station coincided

with the raising of the platform tracks above street level. The station design included a massive balloon

shed covering eleven tracks. The

limestone facade of the old station was ground up and used in the concrete for

the foundation of the new station. The

station opened for business in May 1903, and cost close to $2,000,000.

Construction photographs.

Postcard images and photographs of the station's exterior.

Photographs of the station's interior.

Among the most

famous name trains that terminated at LaSalle were the New York Central's 20th

Century Limited from 1902 until 1967 and the Rock Island-Southern Pacific

Golden State Limited from 1902 until 1968.

Most intercity rail service at La Salle ended on May 1, 1971 when Amtrak

consolidated long-distance services at Union Station. Rock Island opted out of

Amtrak and continued to operate intercity service from LaSalle until 1978. The

station was a set for Alfred Hitchcock's 1959 North by Northwest, starring Cary

Grant and Eva Marie Saint, and in the 1973 movie The Sting starring Paul Newman

and Robert Redford.

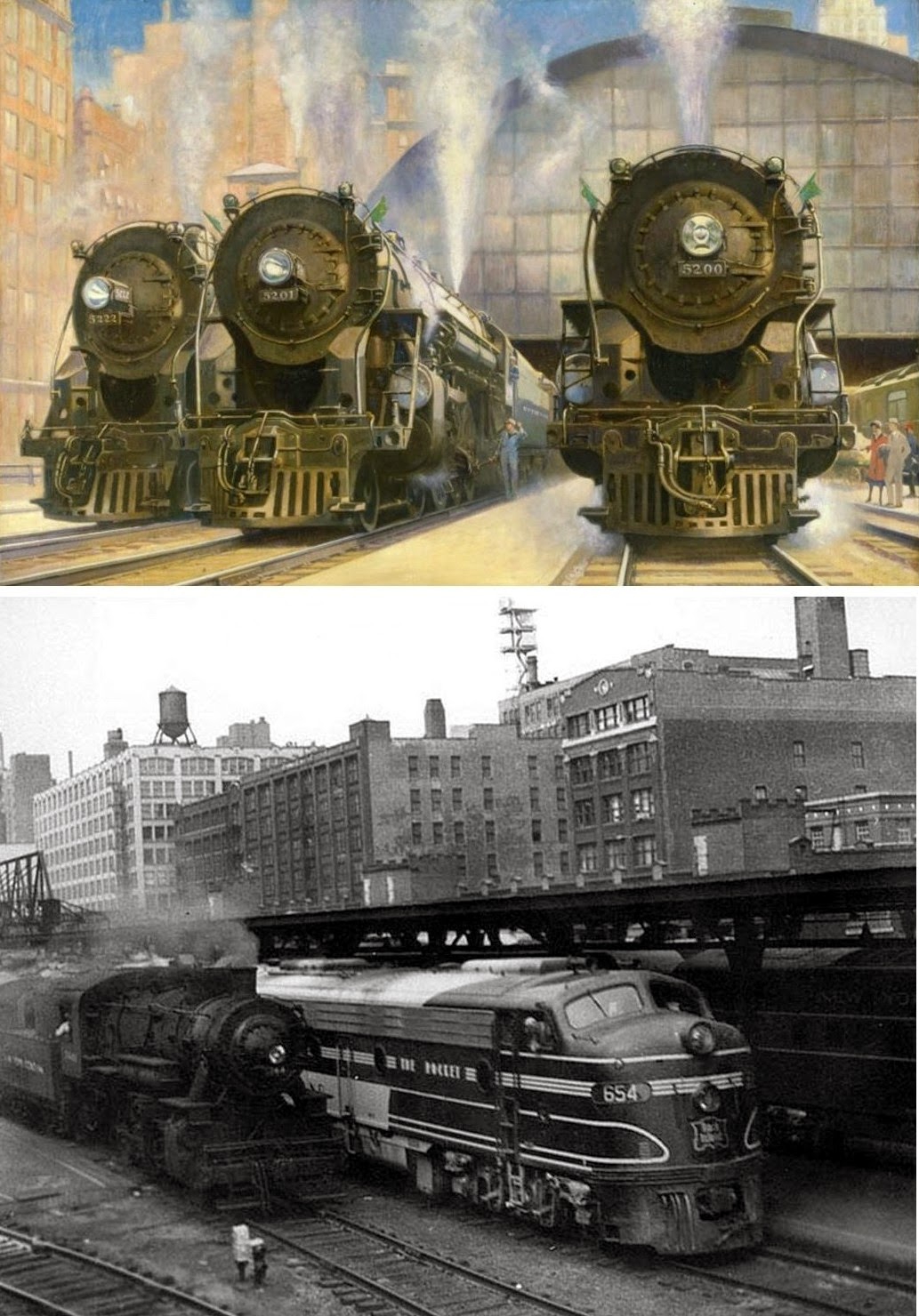

The New York Central's and Rock Island's crack passenger trains operated out of the station.

The Rock Island

fell on hard times in the 1960’s and filed for bankruptcy on March 17, 1975,

and the station continued to serve as a commuter terminal while the bankruptcy

wound its way through the courts. The

plight of the Rock and other commuter services was impetus for the formation of

the Regional Transportation Authority in 1974.

In 1980 the bankruptcy judge liquidated the assets of the railroad, completely

ending operations on March 31, 1980. The

RTA purchased the commuter service that did not include the station, which had

become decrepit after years of deferred maintenance. In 1984 the RTA created Metra as the

operating agency for Chicago’s regional commuter railroad service.

By the time the RTA assumed commuter operations the station had become decrepit.

The Chicago Pacific Corporation, a shell

corporation, was created from the remains of the railroad to sell off its

assets including the station. The

station was then sold to the Chicago Board of Options Exchange who demolished

it in 1981 and replaced it with a new office tower and trading floor. This essentially severed the former station's link with Van Buren Street and pushed the platforms south of Congress Parkway. Exit from the station is now accomplished by two narrow enclosed corridors on the LaSalle Street and Financial Place sides of the new building. A small “station” was added to the building

in 1984.

LaSalle Street Station was replaced by One Financial Place.

In 1985 the Chicago

Pacific Corp. announced plans with other landholders to develop 150 acres in

the area that would require the station to be moved two more blocks south and a

block east. Other plans called for Metra

to move the Rock Island service to Union Station to accommodate the development

plans. Yet another plan called for the

tracks to be depressed below grade along with the platforms and waiting room. Competing

studies weighed the merits of these plans, but Metra and the RTA balked and brought

public and political pressure on the developers to abandon their plans. Metra’s

plans for an improvement project to rehabilitate the platforms were stymied by

this battle. After two years Metra won

its battle and the tracks and platforms remained.

Metra's present day LaSalle Street Station.

Viewed from

today’s perspective the continued presence of the tracks has not been a

hindrance to development in the area.

The plan to move the trains to Union Station would have proved to have been

a transit nightmare as Union Station is now

at capacity. Although only Metra's Rock Island District trains now use LaSalle,

additional service is planned. Metra's proposed Southeast Service would

terminate at LaSalle, and Chicago's massive CREATE infrastructure improvement

program would allow trains from Metra's Southwest Service to use the terminal. In June 2011, The Chicago Department of

Transportation opened the LaSalle/Congress Intermodal Transfer Center alongside

the station as a bus terminal to serve people transferring to CTA buses as well

as Blue Line trains at LaSalle.

The Chicago Transit Authority's Intermodal Transfer Center.

The final lesson in the history of LaSalle Street Station is the failure to incorporate a

new station into the Board of Options Building.

Commuters became an afterthought rather than an asset. When the Chicago & North Western Madison

Street Station was demolished it was replaced by an office building that

included a train station. The station is

filled with the kind of shops and restaurants that one would expect in a modern urban

transportation center. As it stands now

the present LaSalle Street Station is little more than a cattle trough with a

miniscule waiting room. At best it’s a

monument to missed opportunities to create a transportation nexus worthy of its

predecessors.

Development continues to take place despite the presence of the tracks to LaSalle Street Station.