The business of railroading was intertwined with the provincial, municipal politics of Chicago. The necessary permission required to route tracks or build stations wrested with the City Council. In the case of the Galena & Chicago Union Railroad, C&NW’s predecessor, they met with determined opposition from the city’s merchants who saw no value in the idea of a railroad. Farmers were bringing their wagon loads of goods to the city via a number of plank roads. While in Chicago they spent money. Allowing them the luxury of shipping the goods, without the necessity of traveling with them, was not viewed favorably by those who profited from this arrangement. Of course, these interests brought pressure to bear on the Council to block the railroad from building a depot with an ordinance.

Chicago's first railroad station. A historic plaque once marked this location.

When it became apparent that the farmer investors of the

G&CU were creating carloads of wheat for shipment to the city, the

resistance crumbled and the ordinance was lifted. In the fall of 1848 the first train station

in Chicago was built at the foot of Canal Street near Kinzie. This rather humble structure included railroad

offices topped by a cupola for the purpose of watching for incoming trains. The low roofed structure behind the depot was

a freight transfer facility. The

station’s location was far outside of the business district and further

isolated by the Chicago River. To

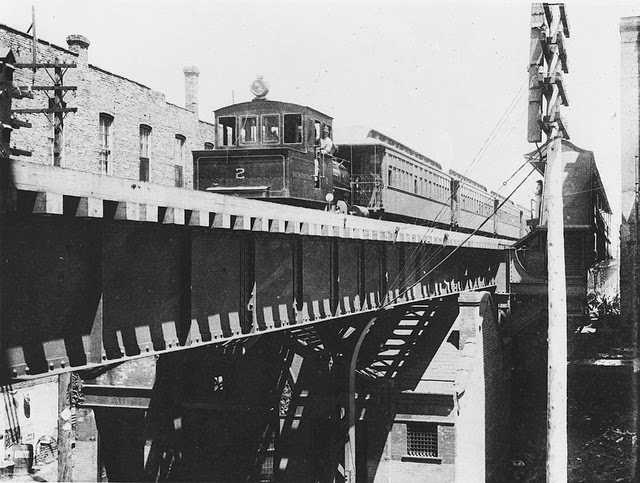

overcome this problem the C&CU needed to bridge the river, which they did

by constructing a pontoon swing bridge over the North branch of the Chicago

River in 1852. This allowed for the

construction of a second station at the Wells Street in 1853.

The G&CU was one-half of what would become the C&NW, the second component was the Chicago, St. Paul and Fon du Lac Railroad, which built its own station on Kinzie Street in 1856. The station would serve the railroad until it’s consolidation with the G&CU in 1864. The building was eventually moved, and survived as a warehouse well into the 20th century.

The North Western's first Wells Street Station (l) later expanded (r).

The new Wells Street Station was more

substantial than its wooden predecessor, which was converted into an employee

reading room. Built of brick and stone

it was later expanded with the addition of a third story. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 burned both

the Wells and Kinzie Street buildings.

Planning began for a more substantial replacement to accommodate the

railroad’s growing passenger and commuter business.

Second Wells Street Station. Image on right shows station annex for commuter traffic.

The new terminal, designed by architect W.W. Boyington (most noted for his iconic Chicago Water Tower) opened in 1881. This Gothic pile of red brick was a more fitting symbol of the growing power of the railroad. Its style points to a problem architects began to confront. What should a train station look like? Aside from housing the functions of the passenger business and the needs of those patrons, what architectural style was best suited for this new type of structure. Depending on the date of construction, Chicago’s stations would follow the popular styles of the era they were built.

The Wells Street Station lived a brief life of a little over

20 years. A number of problems arose

with the site. The C&NW had

extensive land holdings along the river and had built an expansive freight business

that was now mingled with the passenger and commuter trains. The explosive growth of the commuter service

required an annex be added to the original station, but it too proved inadequate

to handle the business. The third problem

was the access to the station via a single bridge over the Chicago River. The original pontoon bridge had three separate

replacements, but the amount of river traffic presented a major problem. The bridge was open frequently, ships having priority of passage, creating havoc with train schedules. Railroad President Marvin Hughitt decided

upon a bold plan that would completely reconfigure the C&NW’s Chicago

Terminal operations. That plan included

the construction of a new, state-of-the-art station located at Madison and

Canal Streets. The result would be an

engineering marvel of efficiency.

Hughitt called upon the architectural firm of Frost and

Granger for the design of the new station.

Charles Sumner Frost and Alfred Hoyt Granger were well known to Hughitt;

they were his son-in-laws. Over time the

partnership designed over 127 buildings for the C&NW, and the firm was

noted for its stations for various railroads.

Construction began in 1909 and was completed in 1911. In accordance with Chicago’s track elevation

ordinances, the approach tracks and platforms were above street level. The station complex itself, including the

massive power house covered 4 square city blocks. The architects chose a classical Roman style, much along the lines of the buildings popularized by the Chicago World's Fair of 1893.

Areas under the tracks were devoted to baggage and mail handling. The station itself contained a massive, vaulted waiting room covered with Guasatvino tiling. Suburban commuters could leave without entering the station proper via two separate concourses. Numerous amenities were included for those passengers using the North Western’s long distance trains.

Postcard views of the interior of the Madison Street Station.

Areas under the tracks were devoted to baggage and mail handling. The station itself contained a massive, vaulted waiting room covered with Guasatvino tiling. Suburban commuters could leave without entering the station proper via two separate concourses. Numerous amenities were included for those passengers using the North Western’s long distance trains.

The station was designed to handle a volume of traffic that

never really developed. With the

assumption of long distance passenger service by Amtrak, the station became a

commuter only operation. The grand staircase

was covered over with a coffee shop, and the lower level converted to railroad

office space. As the Loop business

district expanded west of the river, the North Western saw an opportunity to

cash in on their property and sell the main station to developers. Plans were announced to demolish the station

and replace it with an office tower including a new station. After a spirited battle by a small group of

preservationists, the Chicago Landmarks Commission declined to recommend the

building for landmark status. It was

demolished in 1984.

The new building, designed by Helmut Jahn, was completed in 1987. The station was renamed the Ogilvie Transportation Center, and contains the original clock from the 1911 station’s concourse.

The Citicorp Building and Ogilvie Transportation Center.

Photo credits: top left, Mark2400; top right, Clark Maxwell; bottom, neverphoto.com

The trains sheds that covered the tracks were removed because of structural deficiencies and replaced by Metra, the commuter rail agency. Commuter service is now operated by the Union Pacific Railroad under contract with Metra.

Left, Suburban Concourse; right, new train sheds.

Metra also redeveloped the ground level Suburban Concourse into the ‘Metra Market’ of shops and a French themed grocery store. The power house, along with the platform curtain walls, are the last standing remnants of the station. The Power House was ironically designated a city landmark in 2006, and has been converted to house various businesses.

The platform curtain walls were retained. This period photograph shows the Washington Street underpass.

Station powerhouse.