As I mentioned in an earlier post, the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago was the city's great coming out celebration. The city's prideful boasts earned it the enmity of the New York City press, and the eternal sobriquet as "The Windy City" for the hot air generated by the city's boosters. Much of the historical discussion of the Fair revolves around it's architecture (for better or worse), the tawdry side show of the Midway, the social implications of the treatment of women and minorities, and even a serial killer who haunted the neighborhoods near the Fair. Little has been written about the role of railroads and the movement of vast crowds who traveled both short and long distances to the event.

Panormaic view of the Fair showing the station tracks and platforms.

Over the one year lifetime of the fair 27.5 million people visited, many arriving by rail from distant parts of the nation. In our age of automobiles it is not difficult to imagine the vast amount of surface parking that would be required to handle the daily flux of fair goers. Moving people to and from the fair took place with four forms of rail transportation: steam railroads, steam powered elevated trains, cable cars and electric trolley service. A grand station was built on the southwest edge of the fairgrounds to handle the passengers traveling by railroad. Numerous platforms led to the classically styled station "headhouse". At the headhouse visitors could make a connection to the electrically powered Intramural Railroad that traveled the length of the fairgrounds.

Fair passengers loading at the IC Van Buren Station in downtown Chicago.

The steam railroad most involved in the day-to-day shuttling of passengers was the Illinois Central (IC). From a number of stations in downtown, passengers could board specially built "all door" passenger cars for the trip to the fairgrounds. The cars were derisively known as "cattle cars" for their crude accommodations. The ever resourceful IC had designed them for eventual conversion to freight cars after the fair, lending some credence to their nickname. On October 8, 1893 the railroad hauled a total of 541,312 commuters and fair goers, setting an unsurpassed record for a single day.

Locomotive 201, operated by Casey Jones and preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum

Photograph by David Fullarton

The cars were pulled by diminutive suburban locomotives designed to operate without the necessity of turning the locomotive for the boiler to face forward for the return trip. The IC gathered engineers from around the system to meet the demand for frequent trains, including one John Luther "Casey" Jones whose death in a wreck years later would propel him into folklore legend. In preparation for the fair the IC had also elevated a portion of it's track above street level, adding new express tracks to handle the volume of trains. A branch from the main track at 71st Street would lead to the Fair's station. A direct connection was also provided by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Other railroads would run special "Exposition Flyers" express trains to the city.

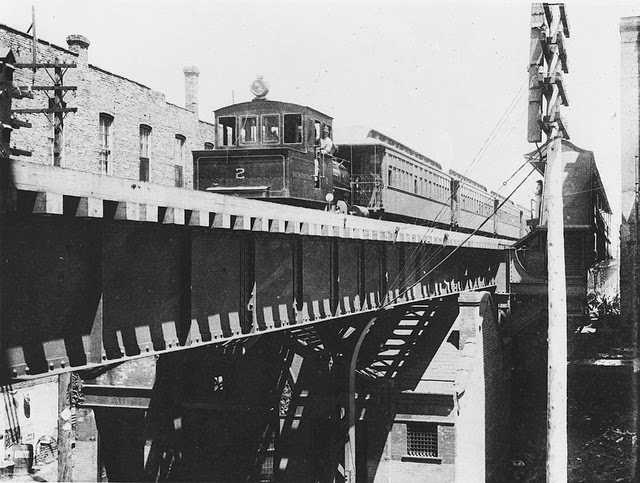

South Side Elevated train.

Cable cars were put to the test on the Fair's busiest day.

The Calumet Electric Street Railway operated streetcars before the City of Chicago.

The South Side Elevated train, also known as the "Alley El", was completed in 1892 and then extended to the fairgrounds in Jackson Park. Their terminal station was situated between the railroad station and the Transportation Exhibits Building. It too connected with the Intramural train. Much like the IC, the elevated trains were pulled by diminutive steam locomotives known by the last name of their inventor Mathias Forney. Chicago's cable car system, which predated electric streetcars, ran to the Fair as well. Finally the electric streetcars of the recently completed Calumet Electric Railway connected residents from suburbs and towns to the south of the city with the Jackson park site. The Fair was well-served by the various forms of rail transportation.

Intramural Railroad train passing the windmill exhibit.

Within the Fair itself the electrically powered Intramural Railway, which shuttled passengers between the various exhibition halls, was a harbinger of the future of urban public transportation. Operating on elevated tracks throughout the fairgrounds it presaged the eventual electrification of mass transit systems like the South Side Elevated.

Front elevation of the station.

Station waiting room.

The clocks surrounding the waiting room displayed times from around the world.

The Fair station would probably be ranked as the largest and busiest railroad station in Chicago based on the number of platforms and the volume of traffic handled daily. It's classical styling would portend the architecture of many stations built following the Fair.

Transportation Exhibition Building

It sat in juxtaposition to it's neighbor, the Transportation Exhibition Building designed by Louis Sullivan. In contrast to the station's design that kept with the classical theme of the Fair's architecture, Sullivan's building was a riot of color and ornament. Prior to the Fair Sullivan and his partner Dankmar Adler had designed two stations for the IC, a commuter station at 39th Street in Chicago and the main passenger terminal in New Orleans. Sullivan's brother Albert worked for the IC and was probably responsible for those commissions to the firm.

Built as temporary structures, many of the Fair's buildings succumbed to a series of spectacular fires that laid waste to the abandoned Fair site after it's closure. The Fair did more than represent a fantasy city of the future, a dreamland of canals flanked by ornate buildings designed to awe and amaze. It showed the possibilities of coordinated mass transportation and it's ability to move people with great efficiency.

No comments:

Post a Comment